Context is King

Notes on the SaaSacre

To the individual who enjoys Patagonia vests and the sexual high that increasing shareholder value brings, there is nothing more beautiful than a software subscription business. From 2005-2023, a twinkling flutter of a moment in capitalism’s ascendency, Silicon Valley invented the most powerful business model ever seen on God’s green earth. SaaS seemed divinely sculpted, a kismet meeting between the needs of venture capitalists to deploy capital and of startups that would need Brinks trucks worth of cash to build products. The margins were judicious, ranging above 85%. The terminal value was indisputable, with customers paying you 10% more every year, forever. It simply…worked.

Until last week, when the market said, “Nah.”

$300 billion in software companies’ market capitalizations vanished, affecting everyone from new darlings like Figma to legacy giants like Salesforce. While the market is mysterious, this selloff is likely due to fears over AI generated code decreasing the value of software companies. Why buy a CRM when you can just make one?

This thesis is too simplistic. In the idea’s defense, there is lots of data to make it seem like that is right. Code is looking like more of a commodity input—4% of GitHub commits are already generated by Claude Code, with SemiAnalysis forecasting that to hit 20% by the end of the year. In my own experimentation, it is remarkably easy to generate applications shaped specifically to my needs. If you give Claude a set of instructions, it can do a halfway decent job of recreating your digital labor.

AI doesn’t make software companies less valuable. It simply makes a different group of software companies more valuable. AI increases the power of software, not decreases it, and AI moves where in the stack the value lives.

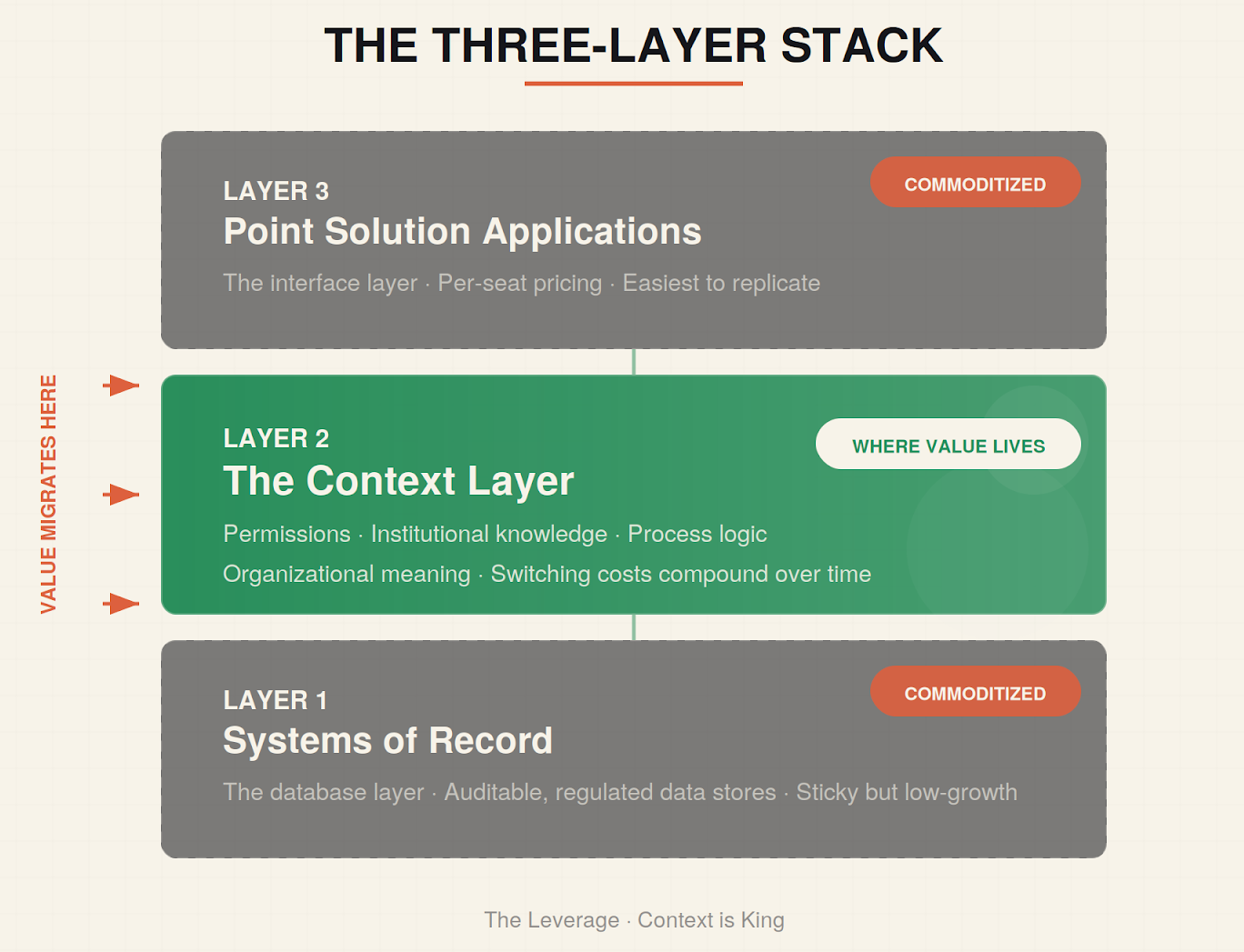

The SaaSacre is partially justified. Many of the SaaS giants of yesteryear should be valued less. But what’s actually happening is a culling of the herd, a separation. Software is splitting into three layers with fundamentally different economics. Two of those layers are getting commoditized. The third—a layer that barely existed before AI—is where the value migrates. I’m calling it the context layer.

The valuation problem

To understand my idea, first we need to establish why the generic software companies aren’t as valuable as they used to be. The answer is threefold:

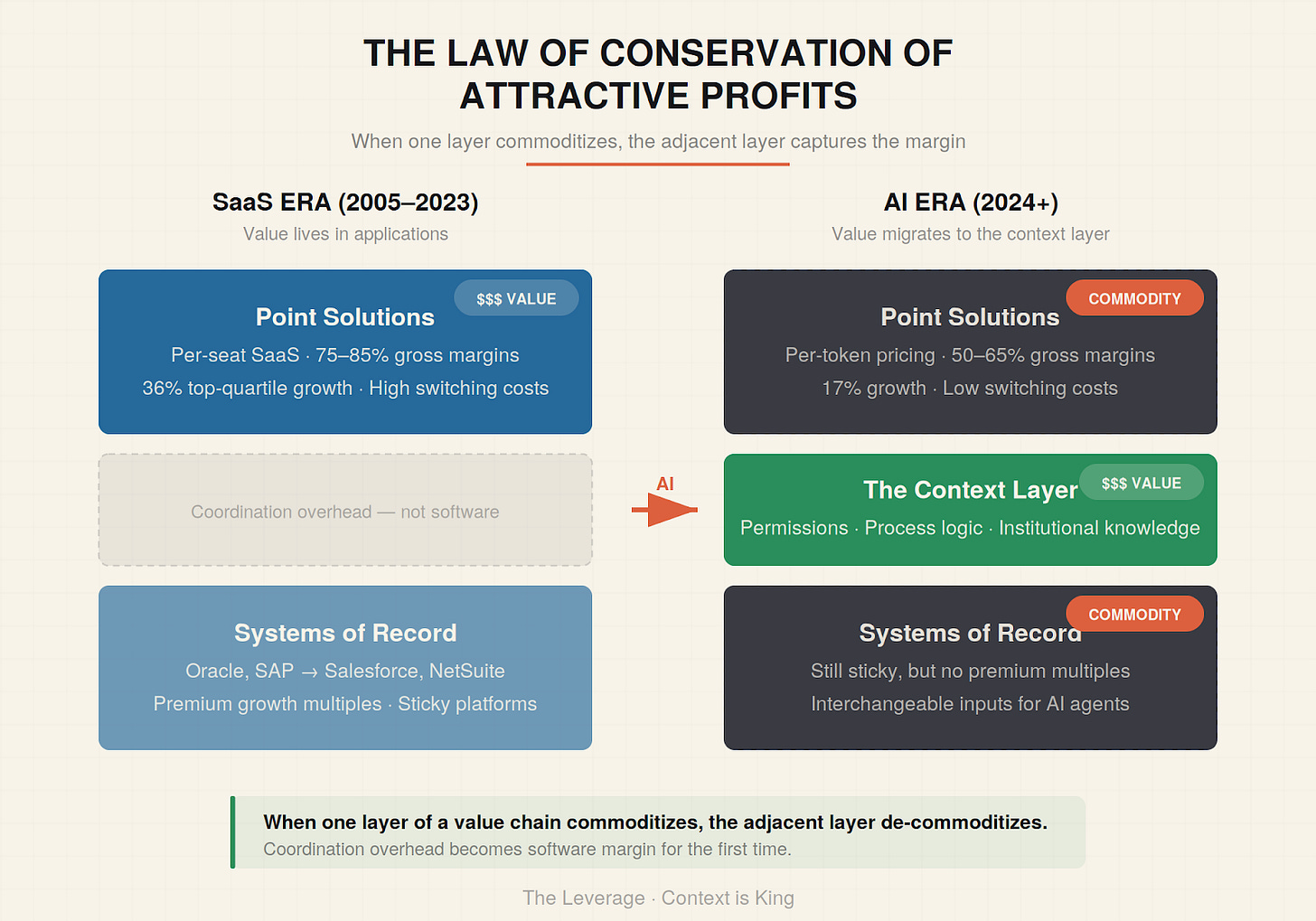

The growth sucks: The top quartile of public SaaS companies today grows slower than the bottom quartile did in 2016. Public SaaS growth halved from 36% to 17% since 2023. Growth is king in technology and these companies don’t have the juice anymore. AI native private companies are where much of the growth in software markets are happening.

The margins are structurally worse: In SaaS, you built it once, and distributed/used it at zero marginal cost per additional customer. In AI-land, you build it once, distribution is more expensive, and each use has a marginal cost. AI-first applications currently operate at 50-65% gross margins, not the 75-85% that justified SaaS premium multiples. Importantly, I would expect these gross margins to improve over time as the cost of intelligence decreases. But that doesn’t matter! That there is a “cost-per-action” associated with the usage of your software dramatically reworks the economic logic.

Switching costs are decreasing, wrecking SaaS platform’s strategic power: This is the underappreciated one. LLMs make it much, much easier to switch data over to a new application. Switching costs are moved to data access and organizational context. There are still good reasons to not vibe code a new application—either due to the opportunity cost or you want to let other platforms be responsible for certain types of risk, such as payments or user identity, really anything where being wrong is catastrophic. But that is a small subset in the world of software! And as agents improve, the organizational context will get easier to switch over too.

Essentially, this compresses every lever in the typical SaaS company’s valuation. Growth, margin, and terminal value are the three things that mostly determine a company’s long-term worth. For the majority of SaaS companies, those are materially worse and will not improve.

But this also introduces a paradox: How can AI simultaneously make software significantly more useful while making it a materially worse business? Does it all just go to consumer surplus? In answering these questions, we can understand what the context layer is and why it is so valuable.

The three-layer stack

OpenAI’s new Frontier platform describes itself as an “intelligence layer” that connects “siloed data warehouses, CRM systems, ticketing tools, and internal applications.” While this does read like secret diary entries of an MBA, behind the jargon is something important. The platform’s goal is to make every software company commodity plumbing. Simply dumb pieces of software that are there to help pipe intelligence around the company correctly.

Frontier, and other platforms like it, simplify the tech stack into three layers:

Layer 1: Systems of Record (the database layer). The auditable, regulated data stores. Financial ledgers, healthcare records, compliance systems. Enterprises aren’t replacing these — they’re layering intelligence around them. Oracle and SAP didn’t die when we switched to cloud, but they stopped commanding premium growth multiples. So too with cloud systems of record like Salesforce, Netsuite, etc. They are sticky, hard to sell, and are subject to increased competition, but these databases have to exist so AI agents can have something to reference.

Layer 2: Point solution applications (the interface layer). The software humans interact with directly. Analytics packages on top of systems of record or project management tools, the stuff that is defined by per-seat pricing. This is the true SaaSacre zone. Tools that serve an individual user, that have no complex security or permissioning needs are doomed because they are relatively simple to spin up.

The world that many SaaS companies were designed for simply doesn’t exist anymore. A significant portion of their workflow can/will be done by agents, driving value away from the software provider and towards the token provider. Legacy providers have bridged this gap with their pricing by bundling per seat human subscriptions with a per token credit system. However new entrants are leaning all the way into it, not bothering to charge per seat anymore and just charging on the basis of tokens used.

But we should strive to be very, very precise here: generating code is commoditized. Governing code in production—knowing what should exist, what databases/systems of records it connects to, who’s allowed to change it—is not. And those crucial questions are only answerable in the context layer.

Layer 3: The Context Layer (the new middle).

The industry already has a name for the space between databases and applications: they’re calling it the “orchestration layer.” But orchestration is just a fancy word for a type of plumbing, and plumbing commoditizes fast. All the current leaders from startups like LangChain, to MCP, or even Google’s agents protocol are racing toward interoperability. The orchestration frameworks will be cheap. What won’t be cheap is what directs the orchestration. The institutional knowledge that tells agents what to do, in what order, and whether they’re allowed to do it.

Before AI, every company had an invisible, accidental version of this to direct humans: the email threads, wiki pages, Slack channels, onboarding docs, and tribal knowledge where organizational truth actually lived. It was never structured. Never searchable. Never maintained. It was just the ugly overhead that required companies to hire more people than they wanted.

After AI, this overhead becomes real software, and it becomes the most important software in the stack. Not because the individual emails are all that precious, but because it’s the raw material for a living model of how your organization actually operates. Who has access to what data, who can do what with it, what sequence of steps actually gets a deal closed or an incident resolved. The context layer is the directing layer, the thing that makes the difference between an agent that takes action and an agent that takes the right action. Best of all, this is a compounding asset. Every time an agent executes a workflow, it generates traces that feed back into the context layer, making the next execution smarter.

That’s context. Context is the institutional knowledge that makes coordination valuable. Systems of record can’t provide it—they store data, not meaning. Endpoint applications can’t provide it—they’re just interfaces restricted to their own domain. The context layer is what makes AI agents productive instead of just active. It is the context of how humans work, but over time, it becomes the context of how agents work even better.

You could argue this is just a fancy way to describe a bunch of markdown files. After all, Anthropic shipped its Cowork plugins as literally that. But there’s a critical difference between context you can write down and context that has to be learned. A markdown file can describe your sales process. It can’t encode that deals over $500K stall when legal reviews before procurement, or that your best AE skips the discovery call for inbound leads from existing customers. That kind of process knowledge doesn’t live in a document. It emerges from thousands of workflows executed over time. The markdown file is a snapshot.

Context is what gets the margin that SaaS lost

The playbook for what happens next was written in 2003. (Nobody in Silicon Valley has read it because it wasn’t a tweet.) Clayton Christensen called it the Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits: when one layer of a value chain commoditizes, the adjacent layer de-commoditizes. IBM’s hardware commoditized, and value migrated to Intel and Microsoft. If applications and systems of record just become the cost of the tokens to create them, and are thus commoditized, the value must migrate to the layer between them.

The reason is structural. At any point in time, there is one thing that is the main bottleneck in a technology stack. Everything else gets cheaper and more interchangeable so that bottleneck can be solved. Right now, the thing that matters most is the connection between how AI models are trained and the agent systems that actually use them. That’s where the real performance gains are. For that connection to improve, everything around it has to get out of the way. Databases become interchangeable inputs. Applications become disposable interfaces. Building software isn’t the hard part anymore. Directing it is. The context layer sits at the new bottleneck.

Here’s the important part: the context layer doesn’t fully compete with existing software spend. It replaces coordination overhead that companies just accepted. It takes money from the payroll budget, not the IT one. If that sounds too clean, consider what the alternative looks like where you pay a bunch of MBAs to do fake email jobs and make slides, all just to make sure that your company doesn’t go off the rails.

Most importantly, it compounds. Every other layer is getting easier to swap out. The context layer only gets harder. The more an organization’s nuance gets encoded—definitions, process logic, team-specific meaning—the more switching costs increase.

The context layer increases the importance of software by turning a category of organizational cost that was previously just called “overhead” into software margin for the first time.

The battle for the context layer

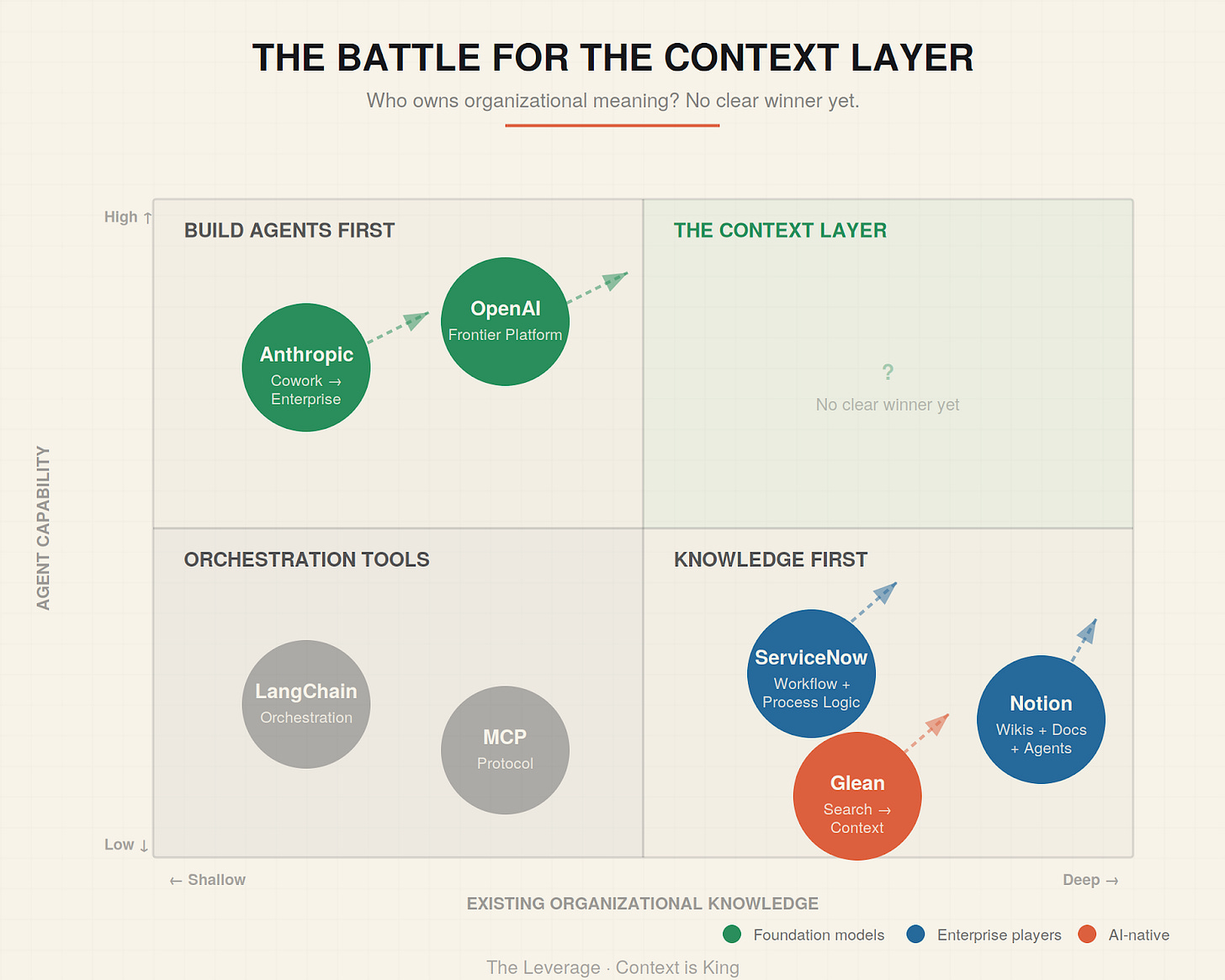

The unusual thing about this moment is that the biggest question in enterprise software is genuinely unanswered. There is a trillion dollars sitting on the ground, waiting for someone to pick it up. There are no clear winners yet. This is mostly because the details of the context layer are incredibly murky right now. We can look at the primary competitors as a lens by which to interpret the potential sources of power.

In traditional SaaS, ServiceNow has the deepest enterprise workflow penetration and just announced collaborations with both OpenAI and Anthropic—it already holds decision logic and process definitions for thousands of large organizations. Notion holds institutional knowledge for a different segment: the companies that run on wikis, docs, and databases. They have a new agents product coming soon that will directly target the context layer. Glean is evolving enterprise search into enterprise context — starting from the problem of “find what we already know” and building toward “know what we mean.” Their bet is that if you can find the organizational knowledge, adding agents on top is a natural extension.

The foundation models are also building towards this. OpenAI Frontier wants to be the semantic operating system connecting databases, CRMs, and internal apps, then deploying agents that accumulate institutional context over time. Anthropic’s Cowork plugins target professional workflows directly, bypassing the application layer entirely. Their bet is that if you build the most capable agents, the organizational knowledge accumulates to you. It is easy to see them extending Cowork into a true enterprise platform.

The question that no one knows the answer to is this: Does the context layer get owned by the company that already holds the knowledge, or the company that builds the most capable agents? The answer probably varies by company size, industry, and how centralized their existing knowledge infrastructure is. But the battle for this layer is now the most important strategic competition in enterprise software.

The close

Christensen’s law says that when a layer commoditizes, the adjacent layer captures the margin. Code is commoditizing. Databases are commoditizing. The layer between them—the one that holds organizational meaning, permissions, and institutional judgment—is where the new value forms. The SaaSacre isn’t the death of software. It’s the birth of the layer that makes software actually work. Systems of record are just databases. Endpoint applications are just code. And both of them are just tokens. Context is king.

Thank you to Akshay Kothari, Buck, Tina He, Nathan Baschez, and a few others who wanted to remain anonymous for their feedback on this idea! They are all worth a follow.