The Private Markets Are Broken

Will Robinhood be able to fix them?

Vladimir Tenev, CEO and co-founder of finance app Robinhood, is bedecked in a black ascot, white pinstripe suit, and dress shoes lifted with a one-inch heel. He’s standing in front of a marble pool in the South of France, preaching the gospel of capitalism. Now, officially, residents of the European Union will be able to use Robinhood to trade “tokenized stock assets.”

Those are nonsense words, but the crowd still goes wild. What he is actually saying is this: When you buy a normal stock, you are purchasing a portion of a company and the legal rights associated with it. When you buy a “tokenized stock asset,” you are buying a crypto thingy that directly mirrors the financial performance of that stock without any of the associated legal rights.

The lack of legal rights isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Tokenization allows investors synthetic access to the financial performance of a company that they normally wouldn’t be able to purchase a piece of. For Robinhood’s European users, who live in countries where regulations make it difficult to buy stocks in the U.S., Tenev’s announcement means easier access to U.S. stocks. And why wouldn’t they want to invest in even a synthetic version of the best-performing stock market in the world?

The American stock market, of course, comes with its specific nuances. One is that American companies are staying private for longer than ever before, meaning that regular people can’t invest in some of the highest-performing companies of our time. America’s drippiest CEO understands this. The new announcement doesn’t just open up synthetic access to public companies. It also tokenizes private company stock, starting with OpenAI and SpaceX.

There’s a part of me that likes what Robinhood is gesturing at. Regular people can now own a token that represents a stock in one of these companies. Getting everyday people access to the tools of wealth creation—in careful, thoughtful ways—means we have a world where value is more equitably distributed. And this was impossible to do heretofore.

However, I think Tenev’s announcement is more of a marketing stunt than some grand, democratizing solution. Think of it this way: OpenAI gives 100 apples to employees and says they can only resell those apples with OpenAI’s direct permission. Once a year, when the apples are tender enough, there will be a “tender offer,” where Apple owners are allowed to sell their apples to pre-approved buyers—like investors from Sequoia and individuals with enough money to get the accredited investor stamp. Not a big pool.

And maybe you’re an apple-holding employee who needs money outside the small, annual window. So a particularly inventive degenerate said “bet” and made a basket company that just so happens to hold those apples. The basket is an SPV and the apples are that employee’s equity in OpenAI. OpenAI can do nothing to prevent the basket-of-apples SPV from being sold to the highest bidder.

This is what Robinhood’s new announcement capitalizes on. The company is able to offer these tokenized shares through its ownership in a basket company. The apples are real, but the tokenized stocks Robinhood’s users are buying are just fictional slices of apple put on the blockchain.

Unfortunately, as anyone involved with one of these schemes will tell you, public SPVs come with a myriad of problems. The demand for apples will almost certainly outstrip the amount in the basket. People want access to some semblance of these stocks because these companies are sexy. But baskets cost money, meaning the SPV-held shares will be more expensive than what people can afford to buy in a normal tender offer. And because demand will certainly outstrip supply, the apples in the basket eventually will be valued far above what the stocks would be worth in an OpenAI approved tender offer.

Let me take you to an even crazier solution. The potential fix to this is known as synthetic tokenized stocks. Robinhood could start selling beans that track the price of an apple. You may say: “Why Evan, what is the relationship between beans and apples?” To which I would reply, “Shut up and look at his cool pinstripe suit, ya nerd.” The point is that the beans are made up, the price at which they trade to apples is made up, and purchasing beans is just gambling on the future price of apples. If demand is what I think it’ll be, Robinhood may soon be in the synthetic stock and bean business.

Baskets. Beans. Chalkboards and Italian marble. When markets get this convoluted, it is for one simple reason: Demand far, far outstrips supply. Robinhood is tapping into a serious desire shared by many people: They want to invest in the bundles of wealth that private companies are producing. Unfortunately, this problem is not going away.

Funding is friction

Companies are pretty rational. The reason they don’t go public and sell equity in the public markets is because it is cheaper to raise it from private investors. It's not that simple, but it kinda is. Companies like Stripe, SpaceX, Databricks, Canva, or Bytedance are a decade plus into their journey and show no inclinations to go public simply because raising from private capital costs less. So, if we understand exactly how staying private is cheaper than going public, we can see how the problem will develop over the next few years.

Valuations

“All I do is tell them I have a term sheet from a Tier 1 VC, and then the rest of the term sheets follow. VCs are sheep.” This was how one AI founder explained fundraising to me. In private markets, founders can create artificial interest in their deal, colloquially known as “deal heat,” pushing the price up. The most straightforward explanation is the correct one here: Companies stay private because the valuations that they are able to get are far, far beyond what they would have access to in the public markets. A good SaaS company today on the public markets might trade at 25-45x revenue. I regularly see AI deals going for 80-100x on the private markets.

Perhaps more important is time. A great company, one that investors reach a consensus on, can close a deal in a matter of days. The IPO process can take six months to a year. In startup land, where momentum is everything, it is hard to justify spending that much time.

Information rights and timelines

When a company is going public, a key step is the roadshow—a multi-step line dance where the company goes over a pitch deck with prospective investors. These investors are the large investment firms, hedge funds, and mutual funds that will buy huge amounts of shares once the company goes public. The company is looking to find investors who want to buy and hold for a long time so their stock price stays high. Investors are looking for great returns, and only sorta care what the company wants. Each investor is different and can change their mind on a whim.

In private markets, the timeline to selling is legible and within the company's control. Private investors tend to plan on holding for at least 5-7 years, and can only sell when the company has a liquidity event through secondary sales or an IPO. Founders love this because the timeline gives them a much larger window than in public markets to make long-term and aggressive moves. Investors hate this because they want to be able to sell shares without the company's approval, particularly if they’ve held for a long time.

Importantly, neither SPVs or synthetic stocks come with something known as “information rights.” Public market investors receive standardized information—income statements, revenue forecasts, risk factors, all the nitty gritty details contained in a company's IPO documents—that allow competitors and analysts like yours truly to pick apart the company. Private market investors are given nada. Owners of shares contained in an SPV know a grand total of zilch about how a company is doing.

There are some downsides to staying private forever. Employee retention gets hard when you are offering big stock packages with unclear timelines on when these will convert to money. Public markets can help keep companies efficient, because founders are forced to scrutinize their businesses closely during quarterly earning calls. Still, many founders seem to prefer the easy, private life of staying private. Which leads to the natural question, what kind of companies even have this option?

Power law is the only law

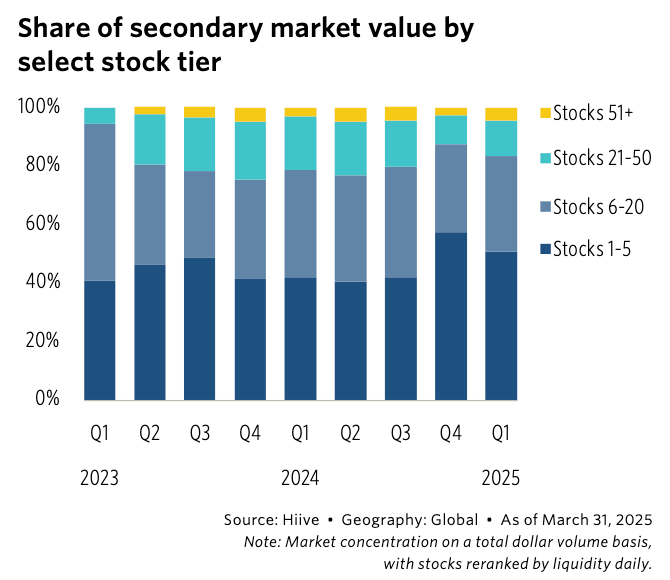

The “we can stay private forever” narrative is only true for a select few companies. You can see that in trading data from Pitchbook, who took a look at the $60 billion in secondary stock sales market. They found that the top 20 companies “accounted for 83.2% of the Q1 2025 trading volume, with the top five representing 50.6%.” This small group of companies has enough investor interest that employees and early investors can sell their shares without ever needing an IPO.

This hard data is also matched by an informal survey I ran among 10 late-stage private investors I know. On average, they estimated that only about 15 tech companies would be able to stay private forever. These are names you are likely familiar with: OpenAI, Databricks, Stripe, SpaceX. Most of these names are either associated with artificial intelligence or defense according to data I was given by Sydecar, a software company that specializes in providing the infrastructure for SPVs. They analyzed the SPVs that had gone through their platform and broke them down by sector.

There is so much value tied up with these companies that investors griped about not being able to sell. One investor, who refused to go on the record with their name, ranted that “Stripe is actively harming Silicon Valley by refusing to go public.”

If we are generous and actually assume there are 50 companies that can stay private forever, that still leaves 1,515 startups valued at over a billion dollars that are left in limbo. The other 97% of companies mostly raised in the 2020-2022 period at the 50-100x revenue valuations they are no longer able to get access to. If they went public, many would have to do a discount in the range of 30-50%, harming the majority of their investors and employees. This is what we call the middle ground between a rock and a hard place. You are either having your stocks sold away in SPVs a la OpenAI or can’t get any liquidity at all.

Companies staying private for this long has implications for every single person in the tech ecosystem. For paid subscribers, I’ll go over the changes that you need to make. I’ll address:

Employee’s careers

Founder’s term sheets

Investors liquidity timelines