The Future Machine

How prediction markets could take over the world

I’m trying something new today. Rather than publish two pieces this week, I decided to experiment with writing one piece that took twice the amount of time and is nearly double the length. At last tally, I’ve read 14 papers, skimmed half a book, listened to five podcasts at 2x speed, and interviewed nine people to get this piece ready for you today. It’s a lot of work! But hopefully you can see the craft and care that went into writing this. Prediction markets are some of the most exciting things happening in technology and finance. To me, they are just as big a deal as AI. Let me know what you think, I can’t do my job without feedback from you.

- Evan

How do you figure out the truth? For example, how do you determine whether Jeffrey Epstein killed himself? You could potentially trust the wisdom of the crowds. For example, a July 9, 2025 poll of 7,237 Americans found that 39% of respondents believed that he was murdered.

However, my instincts tell me that the theory that there is a global cabal of pedophilic elites murdering anyone who can expose them is Mr. Peanut-esque (aka nuts). Who’s right? Me and the nameless Americans who agree with me? The millions of Americans who potentially believe the opposite?

It seems like we’ve only got a few options.

Trust the government (bad)

Trust what we read on the internet (worse)

Trust what a large language model tells us (worser)

Trust media’s reporting (somehow both better and worse)

The issue with all these options is that none of them are directly incentivized to discover the truth. The government wants its populace compliant, social media wants you to spend even more time on the site, the media wants you to buy a subscription or click an ad, and an LLM is a sycophantic weirdo that just wants you to be happy. Now, to be fair, each of those services do frequently produce the truth. Mainstream media in particular is underrated with the amount of rigor and effort that they put into factchecking. But that is more of a happy byproduct of corporate culture than a structural incentive-design choice.

What is needed is a mass-market product where truth is directly incentivized, by design. And now, after nearly 30 years of theorizing and false starts, we have them: functioning prediction markets. The charming part is that they are a fun way to make money, too.

What is a prediction market?

In a prediction market, anyone can place a bet on how an event will culminate. Outcomes are voted on with binary “yes” and “no” options. In practice, a prediction market is like any other speculative market, but instead of betting on the price of something tangible like oil, you can bet on how any event in the entire world will turn out.

The markets are an incredibly unique source of truth. Say, for example, that you wanted to learn about what’s happening with Epstein. You can see the odds of Epstein-related events occurring by pulling open the prediction market of your choice:

According to this market, there is a 7% chance that Jeffrey Epstein's murder will be revealed this year and a 3% chance that he is still alive. These might seem like arbitrary numbers, but they contain something special: The truth has a price attached. Maybe you look at some of these odds and think: “That’s way too low.” Good! Now you can put your money where your mouth is. If you’re right, you have a direct incentive—buckets of profit—to trade on that price and move it in the direction you believe is correct.

Think of it this way: if a media company publishes a huge scandal of a story, and sink a stock, you'll get subscriptions and ad clicks regardless of whether that scandal is real (see Bloomberg and Apple from a few years ago). A prediction market trader could have a belief about Apple, but they won't make a penny unless they are right.

It turns out that if tens of thousands of bettors do this exercise, the price embodies a lot of information and hidden knowledge that other forms of truth discovery don’t have. These markets are so good at predictions that a meta-analysis done in 2020 found that they were more accurate than available alternatives like polls, expert panels, or economic models by about 79% on average. Not bad!

The magic happens because each market consists of four types of participants:

The Platform or/ exchange (e.g., Kalshi or Polymarket). A prediction-market platform is the neutral “casino floor.” It writes the rulebook for each contract, matches buyers and sellers, escrows funds, and adjudicates who gets paid once the real-world outcome is decided. Its revenue comes from tiny per-trade fees, and it doesn’t make money from taking sides of bets.

Market Maker. The market maker is the facilitator. Using algorithms and capital, it continuously posts bids and asks so other traders can get in or out instantly, earning a fraction-of-a-cent spread each time. Big proprietary firms such as Susquehanna (active on Kalshi since April 2024) or dedicated on-chain bots play this role, and without them most markets would be thin or untradeable. Their business is mostly algorithmic trading.

“Dumb Money” This is the swarm of casual or sentiment-driven bettors who trade for fun, curiosity, or a story, not an edge. Their small, sometimes ill-informed orders create the mispricings that make the game worth playing for everyone else. Take the opposite side of dumb money and you’re on the right side more often than not. Paradoxically, prediction markets need this group: Without minnows to gobble up, the sharks go hungry and liquidity evaporates. Unless you have unique data, a novel analytical framework, or have been blessed by Hermes, I have bad news for you—you are the dumb money.

“Smart Money” Smart money is the cadre of information-advantaged traders—quant desks, domain experts, “superforecasters”—who scan for prices that diverge from their models. When they spot a gap, they pounce, empowered by the advantage of size. They nudge the odds toward true probability, pocketing expected value. Their profit motive is the engine that keeps market prices sharp, turning scattered private insights into a publicly visible consensus.

The goal of any platform is to have the correct balance of dumb money, smart money, and market makers. The dumb money provides mispricings, smart money forecasts the truth, and market makers provide liquidity to traders.

Where did betting markets come from?

It isn’t exactly a new idea to bet on future events, nor is it new to find truths in how these bets pan out. Some of the earliest versions of prediction markets took place in the 15th and 16th century papal elections. Italian men would rush around Vatican City, frantically ferrying betting odds to the Roman bankers who were speculating on the next Holy Father. (There was actually a whole cottage industry of Pope-related financial instruments—it was common for businessmen to take out insurance policies against a Pope’s life in case he unexpectedly died and a bill came due.)

In the U.S., between 1868 and 1940, there was a long tradition of betting on presidential elections. Despite them being “illegal” there were daily price quotes in newspapers, with a particular popularity in New York City. These markets were huge, “For brief periods, betting on political outcomes at the Curb Exchange in New York would exceed trading in stocks and bonds.” One year there was roughly $316 million in 2025 dollars being wagered. The markets ended up withering through a combination of stricter legal enforcement, Gallup polling becoming popular in 1936, and literal horse races capturing some of the gambling excitement.

Still, if we were to give credit for prediction markets as they exist today, one man deserves his laurels: Robin Hanson. The associate professor of economics at George Mason University has been arguing for the merits of prediction markets for over twenty years. Through his relationships within the effective altruism community and his blog, he has slowly but surely built adherents within the technology community.

Until just a few years ago though, these prediction markets were mostly theoretical and hadn’t achieved mass adoption. There were markets that used playmoney such as the Foresight Exchange (FX, originally called Idea Futures) which began in the mid-1990s as an online game. Or there were international markets, like Ireland-based Intrade that used real money or were shut down by the U.S. government because officials felt that Intrade was offering unregulated futures contracts. To many—including many government officials—there is little difference between a prediction market and gambling. Both bet on speculative futures. Whenever a market achieves a modicum of popularity, regulators threaten companies with the go-to-jail card from Monopoly.

Online betting marketplaces only had two options: Cozy up to the government, or break the law. A billion-dollar-business has been built using both methods.

The players (and my secret addiction)

I started to really pay attention to prediction markets in the summer of 2020, when Polymarket first opened its doors. I was familiar with Hanson and his work and had followed the space, but for the first time I saw a chance to make real money.

Polymarket had figured out how to get around the U.S. regulation by uh, ignoring the government. Trades on the platform are done via crypto so users can mask their location and identity. It might be illegal, but ya know, don’t ask, don’t tell. As you can guess based on my current profession, I’ve always prided myself on my abilities as an analyst and forecaster, so this seemed like a new way to test myself. By October of that year, I had created an account and started trading.

Within a month, I made $5,000 betting on the U.S. elections cycle. It is hard to describe how intoxicating this was. Do analysis, place bets, make money, repeat.

My prior obsession had been the videogame Overwatch where I rose to the rank of Grandmaster, a top 1% player in the world. (A fact I’m only willing to publicly share because I’m married now and my wife already likes me. She knew what she was getting into.) Playing Polymarket felt the same as playing Overwatch. Yes, there are technical skills necessary to bet on the platform. However, at the highest levels of both Overwatch and Polymarket, your technical skills are best used in understanding the strategies of other bettors. For example, Trump betters were irrationally exuberant in 2020. It’s not clear to me why that was, but the odds were frequently off according to my analysis. There were frequent price disparities between reality and what bettors were buying.

By Christmas, I realized I was hopelessly addicted and had to stop. It's the same reason I don’t bet on sports, drink alcohol, take drugs, or day trade—I have a personality that is prone to hyperfixation.

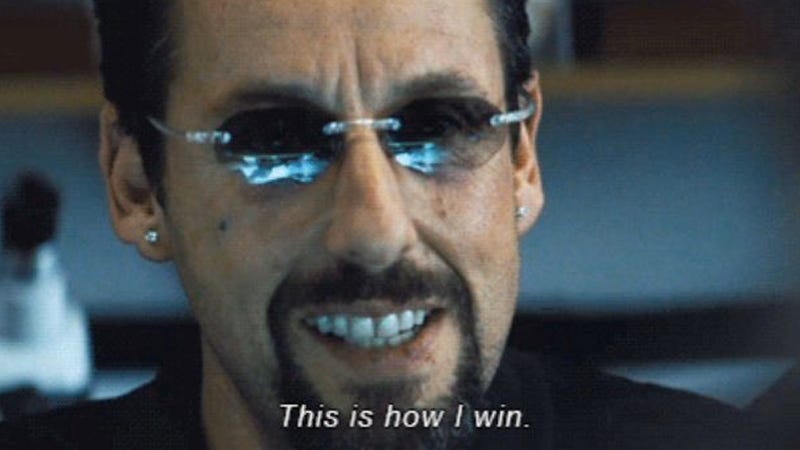

That exact feeling is why Polymarket has to skirt around regulation. For all intents and purposes, this is a speculative marketplace where people gamble their funds on uncertain futures. Essentially, it’s Uncut Gems as a service.

Prediction markets monetize differently than traditional gambling houses. They get paid by taking a small transaction fee from bettors, and let the marketplace set the odds. Casinos set the odds themselves. Still, the user experience is remarkably similar to putting money down for your favorite team.

Polymarket has been punished for its regulatory boldness with an initial ban in the United States in 2022, with Switzerland, France, Poland, Singapore, and Belgium all enacting bans in the years that followed. So the trading I did back then would be illegal for me to do today. These blocks aren’t all that hard to get around with a VPN (this is not financial or legal advice!!). The company is rumored to have just raised $200 million at a $1 billion valuation from Founders Fund. And while the monthly active user count is currently at 242,000, which is 47.6% lower than its all-time, post-election-cycle high from January, traders are wagering much more money. The average traded per account was $4,800 in June versus roughly $2,700 in January.

Kalshi, Polymarket’s primary competitor that started in 2018, took the opposite approach. Rather than try to sidestep regulation via crypto, it spent three years seeking approval from the U.S. government body over futures. Finally, in 2021, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) gave it approval. There have been debates and lawsuits on what types of markets Kalshi is allowed to offer, with sports and politics betting being hotly contested. However, despite its later start, the company raised $185 million at a $2 billion valuation. To increase its coziness to the current administration, it appointed Donald Trump Jr. as an “advisor” in January 2025. The platform did $1.9 billion in trading volume in the second quarter of this year and is growing quickly.

The reason I’m belaboring the regulatory approaches is because of our original question—how do we determine the truth?

How do these markets determine the truth?

On Sunday, I sent out the Weekend Leverage in which I wrote about the current crisis at Polymarket.

“Do you think this is a suit?

This is Ukrainian leader Volodymyr Zelensky, who, famously, has refused to wear a suit while his country is at war with Russia. On Polymarket, a prediction market, there was about $200 million in trading volume being bet that he would wear one in June of 2025 as reported by a “consensus of credible reporting.” The market resolved that no, he did not wear a suit. Which is weird, because dozens of major publications and creators called this outfit a suit.

It is worth talking about how Polymarket determines “the truth.” Polymarket relies on a platform called the UMA Protocol, where holders of the UMA token are told to be an “impartial arbiter of the outcomes of relevant markets.” However, these token holders' voting power is determined by the amount of the token they are holding. If they mark yes, and the market resolves as a yes, they see an increase in their token holdings. If they mark no, they lose some of the tokens they hold. Meaning that when large token holders, whales, swing votes however they deem fit, the smaller holders will pile on after them because they don’t want to lose value, and would like to gain value, and influence. Worse, UMA token holders are also allowed to trade on PolyMarket! They are double incentivized to make the truth into whatever generates profit.”

Because Polymarket’s regulatory approach is decentralized, so too is the way that it determines the truth. The whale-based approach of the UMA token means that the truth is up for purchase in any market where the outcome is ambiguous. It may be that the suit causes a lawsuit (which would suit Kalshi just fine).

In contrast, every contract on Kalshi is drafted by its listings team and must be pre‑cleared by compliance. For each bettable listing, the rules spell out the exact metric, the source agency (e.g., BLS for CPI, NOAA for hurricanes), the cutoff time, and any fallback if the data release is delayed. These rules are part of Kalshi’s government‑approved rulebook—they can’t be changed mid-bet. Trading stops either when the specified data point is published or at a preset “last trade” timestamp.

Kalshi’s operations team pulls the official figure from the pre‑named source agency. If the CPI release says YoY Core CPI was 3.2 %, the answer is an objective “Yes” for any contract that asked “> 3 %?”.

Kalshi listings must anchor to a single, publicly released data series (examples include GDP, CPI, Fed funds decision, NOAA storm category, and Oscars winner). That constraint produces crisp binary resolutions and keeps the exchange in the CFTC’s good graces. Polymarket purposely allows any yes/no statement that can be phrased in text, which is great for breadth, but inevitably invites edge cases and linguistic gray areas. The UMA oracle can still resolve them, but only after a social voting process that is slower and, on rare occasions, contentious. Polymarket has the more intellectually entertaining markets, but Kalshi has ones where you know the answer is clear.

I have a few ethical concerns

The correct way to view gambling is an entertainment product that enhances your enjoyment of current events. For an essay I published in 2022, I interviewed DraftKings customers who discussed being unable to watch sports without gambling because otherwise they felt bored. Putting real money on the line made a Tuesday night throwaway game as important as the Super Bowl.

The problem of prediction markets is in how they think about market participants. Smart money will almost always appear whenever there is profit available, so the goal for these marketplaces becomes attracting as much dumb money as possible. To do so, both companies have engaged in less than savory marketing practices. Polymarket built an entire social media campaign around using the outdated and abhorrent word “retard,” and Kalshi employees asked social media influencers to trash-talk Polymarket after its CEO got into legal trouble. Controversy is an excellent way to gather attention, but there is a contrast between the righteous goal of truth, and the murky nature of gathering enough user density to get there.

Sports is likely the primary sin of these platforms. They are the devil’s deal. By opening up sports futures, Kalshi has dramatically increased its regulatory risk because it will be relying on their federal protector in the CFTC to overrule sports gambling laws in individual states. It will also end up flooding the website with “dumb” money that inserts profit margin into trades that are unrelated to sports.

Prediction markets are fascinatingly paradoxical. It's all about adverse selection, a fancy way of saying that the person betting against you probably knows something you don't.

Usually, markets thrive on this kind of asymmetry because dumb money tends to be plentiful—overconfident and frequently incorrect. The market maker looks at these bettors and says, "I'm smarter than the average bettor," and statistically, they’re often right.

But here’s the catch: The more specific—or finely sliced—a prediction market gets, the more it disproportionately attracts smart money, those participants who actually know something concrete, real, and valuable. Imagine a market on something incredibly niche, like "Will Japan announce a major shift in monetary policy next April?" Suddenly, bettors aren't random overconfident generalists—they’re smart money, insiders at the Bank of Japan or at least someone who just had coffee with one. As the market maker, every time someone wants to bet "yes" on that hyper-specific event, your Spidey sense tingles, and you start suspecting they have privileged insight.

Who is that at the door? Is it Martha Stewart frantically warning us about the dangers of insider trading? Not to worry—they probably won’t do anything about it. Any market where some participants may learn outcome-relevant facts before the rest (or can directly influence the outcome) is vulnerable to “insider” trading, and prediction-market operators theoretically take that risk seriously. In practice, whether it is allowed, detectable, or illegal depends on (i) the regulatory perimeter (CFTC vs. SEC vs. unregulated crypto) and (ii) the desire these markets have for enforcement. No public record shows that Kalshi has ever expelled, suspended, or otherwise disciplined a trader specifically for insider-trading–type misconduct. So far, there’s never been a proven or publicly penalized case of insider trading on Polymarket. To me, the idea neither market has had any insider trading feels akin to my odds for becoming quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys.

This means two contradictory things happen simultaneously. First, the prediction market itself (the platform) becomes smarter and richer with highly specific, actionable intelligence. Second—and here’s the paradox—the market maker panics, understandably, and says, "Whoa, I'm going to widen my spreads to protect myself." But widening spreads dilutes the value—the alpha—of the market’s intelligence. Pretty soon, betting on hyper-specific Japanese monetary policy events becomes less attractive for smart money than simply trading yen futures or Treasury bonds, because those broader markets reliably react to news.

It's this weirdly beautiful dance: The market maker is desperately needed to facilitate trades and ensure liquidity, dumb money is essential to keep the market attractive, and smart money provides the insights that give the platform its predictive power. In the early days of a market, where there is relatively little money involved, and trades are infrequent, the odds are much less reliable. As the market gets closer to resolution, and as trading volumes increase, the odds become more accurate and valuable.

Frankly, we don’t quite know what happens as prediction markets scale up. Will the noise of the crowd drown out the superforecasters? Will whales manipulate markets? I don’t know, but the pursuit of growth at all costs has the risk to destabilize what makes these markets socially compelling, namely a way to put a price on truth.

For paying subscribers to The Leverage, here are five strategies for how to make money via Polymarket.