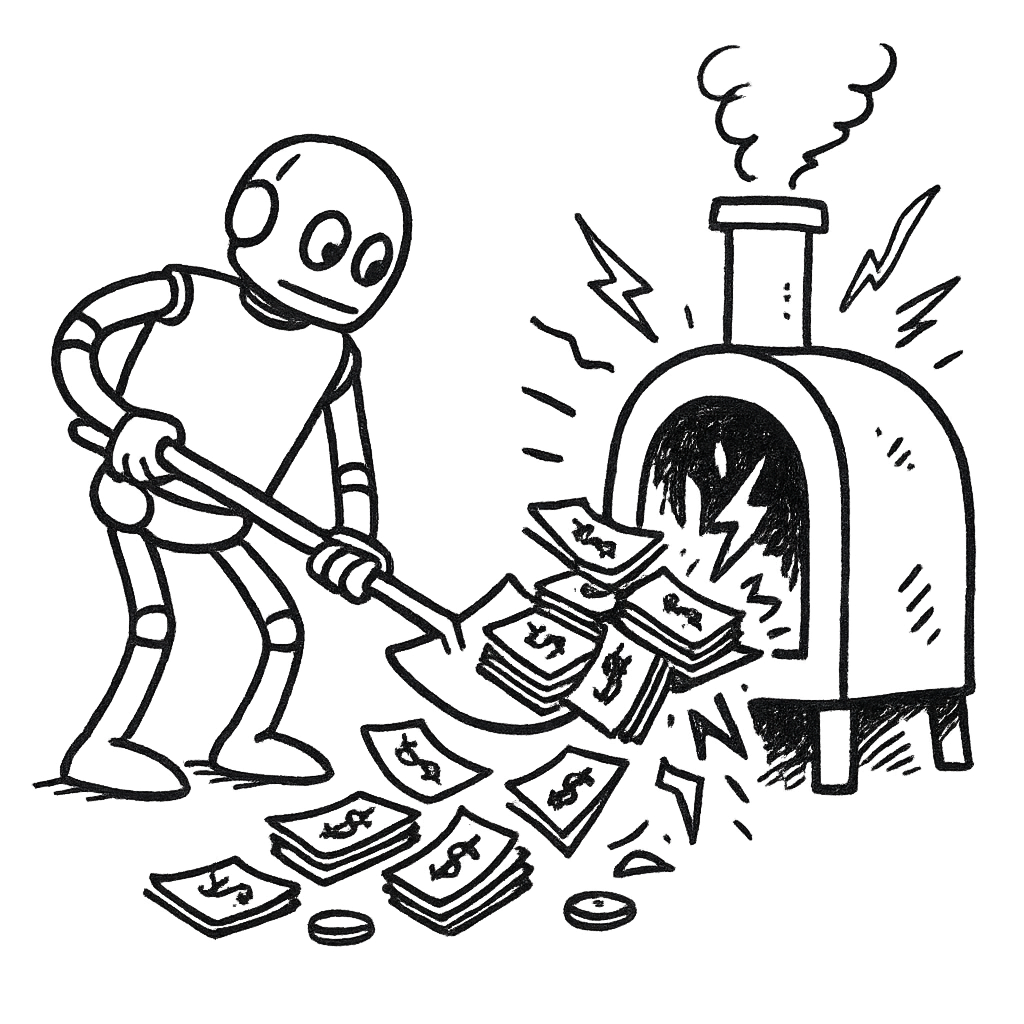

Profit is for Chumps

AI startups should be increasing their spend

For venture-backed startups, the penalty for prudence is irrelevance. When you are dealing with markets that move as fast as AI, with investment capital that starts with a “Billi”, the worst thing you can be is slow.

Despite that, there has been a slew of negative reports detailing how AI wrapper startups like Cursor, Lovable, and Replit are running on t…