A Robot Walks Into a Coffee Shop

Specialized machines crush humanoids at single tasks. The interesting question is why the economics flip when you walk through your front door.

On my frantic, 20-minute drive to Boston Children’s Hospital, I count 23 coffee shops. There is a Dunkin Donuts/Jimmy John’s for when you are craving completely mediocre everything. There are four of those horrible Starbucks where drinks are thrown carelessly on a counter by an out of work STEM grad. There are Greek cafes, private-equity-backed “French bistro” monstrosities, even an independent shop where the owner will kick patrons out if they talk too loud (personally, I think this is a positive). Every flavor, every type of caffeinated beverage, all immediately available for me to try.

They hold no appeal. My daughter is due for an important test; she is crying and scared; I am a little scared too. I’m counting the coffee shops to buttress against the crashing waves of my anxiety.

Finally, we pull into the hospital’s $12 an hour parking garage, and ascend to the lab. As the elevator door dings open, I can’t help but laugh at what greets me.

Make that 24 coffee shops on the way to Boston Children’s Hospital.

This is the Hestia Robotics Coffee Robot C1 PRO, operated by Robo Cafe USA. The manufacturer’s website boasts of it being able to make over 200 drink varieties with the various non-milks, oat, almond, and whatever, all available for consumer’s consumption. You can find similar robots on Alibaba for roughly $50K. That little white arm in the middle moves the coffee from espresso machine to milk frother, slowly connecting a caffeinated potion. By automating the barista’s hands away, you also remove the need for a bathroom, benefits, or breaks. Instead, the human job at coffee shops like the C1 PRO is that of a vending machine dude going from coffee robot to coffee robot, refilling cups and oatmilk. This also means that the ideal entrepreneur of coffee shops won’t be coffee snobs, but instead people with connections in real estate and strong supply chain management experience.

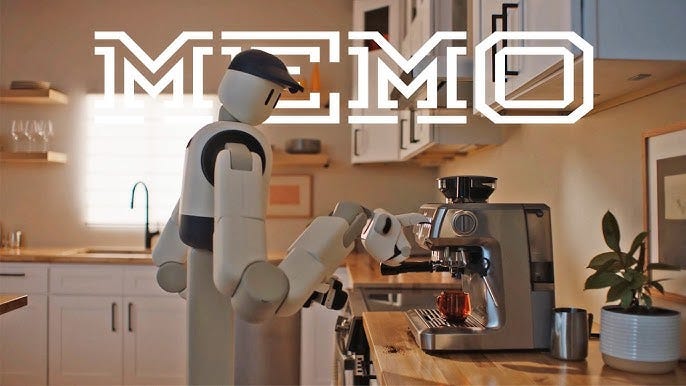

When I write about how robots will soon come crashing into our lives, I’ll usually get some emails from all of you, replete with fear of mass unemployment. This is particularly true in the case when I discuss humanoid robots like the Tesla Optimus or the Sunday Robotics Memo that went viral a few weeks ago on Twitter. In that video, we, once again, see a robot making a cup of coffee.

In this demo video, the robot is operating the Breville Barista Express Espresso Machine, which usually goes for about $700. In interviews, the founders of Sunday Robotics talk about the robot in this video costing about $20,000 for the bill of materials. This usually means the cost of the components and the assembly, with no cost added for operations, marketing, all the mundane stuff that makes a consumer plop down a credit card.

Ultimately, competition in robotics coffee is not just about the labor of pulling a shot of espresso, but for the market structures surrounding that labor.

Take, for example, Blank Street Coffee. This is a venture backed coffee chain that has taken off in the last few years, adding 90 locations since 2020. In my hometown of Boston, there is a constant line of Gen Z customers, wearing big pants, little shirts, and a Labubu dangling from a keychain, lined up out the door.

The company’s strategy is explicitly the automation of barista coffee labor, so they can spend time making specialty drinks like matcha and, more importantly, forming connections with customers. Blank Street employees are friendly! To give baristas the time to say hello, the shops use a Eversys Super Automatic, a coffee machine that uses multiple touchscreens to produce “700 espressos per hour, 8 products at the same time, 350 cappuccinos, and 170 hot water products.” This tool costs about $50,000, similar to what our coffee robot in the hospital cost. Blank Street’s success “automating” away portion of barista’s labor instead allows them to focus on activities more valuable to the customer (saying hi). It turns out that people want the drink to taste good and the service to be friendly, and what percentage of that offering is made by machine versus human isn’t important.

There’s an economic framework that explains why Blank Street works, and it comes from economist David Teece. In 1986, he published a paper called “Profiting from Technological Innovation,” asking a question that’s haunted every startup founder since: when someone invents something new, who actually makes the money?

The answer is likely depressing for my readers who are technical. The inventor usually doesn’t capture the value. The people who own the complementary assets—the distribution, the brand, the real estate, the customer relationships—they’re the ones who get rich. His canonical example is RC Cola, which invented diet cola and then watched Coke and Pepsi steal the entire market using their bottling networks and brand recognition. RC Cola had the innovation while Coca-Cola had everything else.

Apply this idea to our coffee robot in the hospital. The robot costs $50K. The real estate it sits on in Boston Children’s costs... I don’t know, but I’m guessing the hospital isn’t giving away lobby space for free. The supply chain for cups and oat milk and coffee beans requires someone to manage. The robot is the innovation, sure, but the complementary assets are what determine whether this is a business or not.

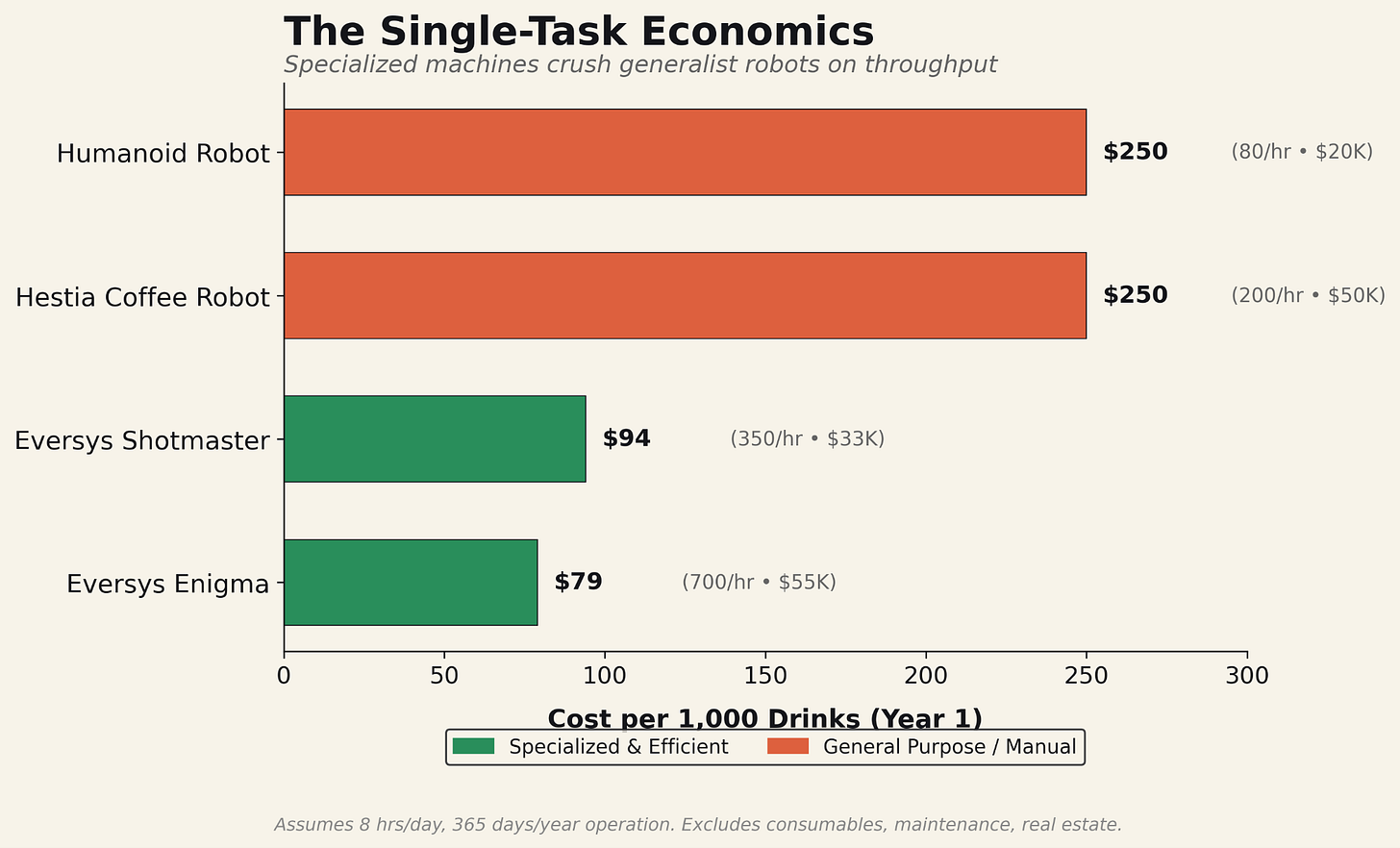

The Sunday Robotics humanoid has the same problem, but worse. Let me show you why with some actual numbers.

The Sunday Robotics demo shows a humanoid operating a $700 Breville machine. In the video, it takes roughly 45 seconds to pull a shot and steam milk—call it 80 drinks per hour if nothing goes wrong, if it never needs to refill beans, if nobody orders anything complicated. The Eversys Shotmaster, which Blank Street uses, does 350 espresso drinks per hour. The Enigma, their higher-end model which is usually deployed at Blank Street, does 700.

At those throughput rates, the math is brutal. Even though the Eversys costs $33,000-55,000 compared to the humanoid’s $20,000 bill of materials, the cost per drink is 3x lower because the machine is optimized for exactly one thing: making coffee fast.

The humanoid’s advantage is generalizability—it can use any tool designed for human hands, so you don’t need to retrofit your infrastructure. But generalizability is a cost advantage (no retrofitting), not a performance advantage. And in a coffee shop, where the unit of value is espressos per hour, performance wins. This is true across almost every high-frequency, single-task commercial application. When you’re optimizing for a single, measurable task, specialization beats generalization by a factor of 3-10x.

That’s the easy part. Specialized machines crush humanoids at single tasks—everyone paying attention already knows this.

The interesting question is why the economics completely invert when you walk through your front door. And the answer matters whether you’re investing in robotics, building in it, or just trying to figure out where the money actually lands.

The portfolio problem and why you’re probably underestimating your household labor by 3x

Three conditions where generalization beats specialization (I call it the Swiss Army Knife threshold)

The smile curve, and why the central question in robotics right now is whether this is smartphones or aircraft

What ATMs did to bank teller employment—it’s not what you think, and it’s probably what happens next