On Stewart Brand's Maintenance

Everything decays. Now what?

Help me out here.

How would you describe a non-fiction book that has the following contents: Diatribes against the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 3 separate diagrams on the proper construction of Dry Stone Walling, one brief anecdote where in which you learn that the author spent “a couple of weeks in France” learning to build said Dry Stone Walling, effusive praise for his favorite manuals ranging in topic from Volkswagen maintenance to childbirth, a comparison of the success of the AK-47 and the failures of the M16 Rifle in Vietnam, 7 different pictures of the Model T car, an explanation of the software platform that has allowed the Ukrainian army to run rings around Russia’s beleaguered forces, and an overview of 12 essential types of corrosion which introduce $2.5 trillion in costs to the global economy.

The way I see it, there are two word choices that would typically be utilized by the Big Book Review™ industrial complex.

Sweeping: of scope, ambition, breadth. The vision of the book is so grand that you can get away with quickly and vaguely pointing to a large variety of topics. (See Sapiens reviews upon release).

Meandering: a word that allows the reviewer to politely point out this book is ass, can’t focus, and has bad pacing. Alternative word choice include eclectic or scattered. (See Sapiens reviews now that everyone has calmed down a bit).

Both of these choices are bad options to describe author Stewart Brand’s Maintenance: Of Everything. It has sweeping scope, yet simultaneously meanders in its arguments. Instead, I would choose a third, more elusive moniker. I would call this book reflecting. Its loose collection of anecdotes is about filling the soul of the reader with enough stories to triangulate the mind into a new worldview, and then allowing the reader to reflect that worldview onto their personal circumstances.

Within that framework, I found the book to be one of the most spiritually enriching technical manuals I’ve ever read. It tends towards overspecificity in its details and vagueness in its conclusions. It has lots of little ideas and a few big ones and that’s all kinda the point. It is a worthy addition to the Tech Canon and a book that all people interested in startups should read.

Here’s why.

How to think about this book

The default path for reviewing non-fiction books is to closely examine their central argument, find if that argument is worthy of praise or condemnation, and write accordingly. And this, admittedly, is my typical process for reviewing non-fiction work about technology.

To apply the same method here, Brand’s central argument is that maintenance is a vastly underestimated and powerful force in our world. It is simultaneously a spiritual pursuit that shapes the individual practitioner, and when an attitude of Maintenance is adopted by a larger society, it allows for the flourishing of its people, most obviously shown off in mechanical combat.

In this regard, the book is unconvincing. The argument is never stated fully, lacks structure, and the end…just doesn’t exist. The last chapter is mostly about Tesla and electric vehicles’ decreased maintenance needs. It then has about two paragraphs’ worth on why horses are cool, and that’s kinda it. I am not a reader that needs their hand held, but I do think some forms of structure strengthen the case.

Additionally, the book has relatively little in the way of studies, macro-analysis, or comparison to other potential forces that could be more important relative to maintenance. Instead, Brand’s writing mostly relies on the strength of its anecdotal evidence to make its case. And, if this was a typical book, by a typical author, I wouldn’t bother to tell you about it.

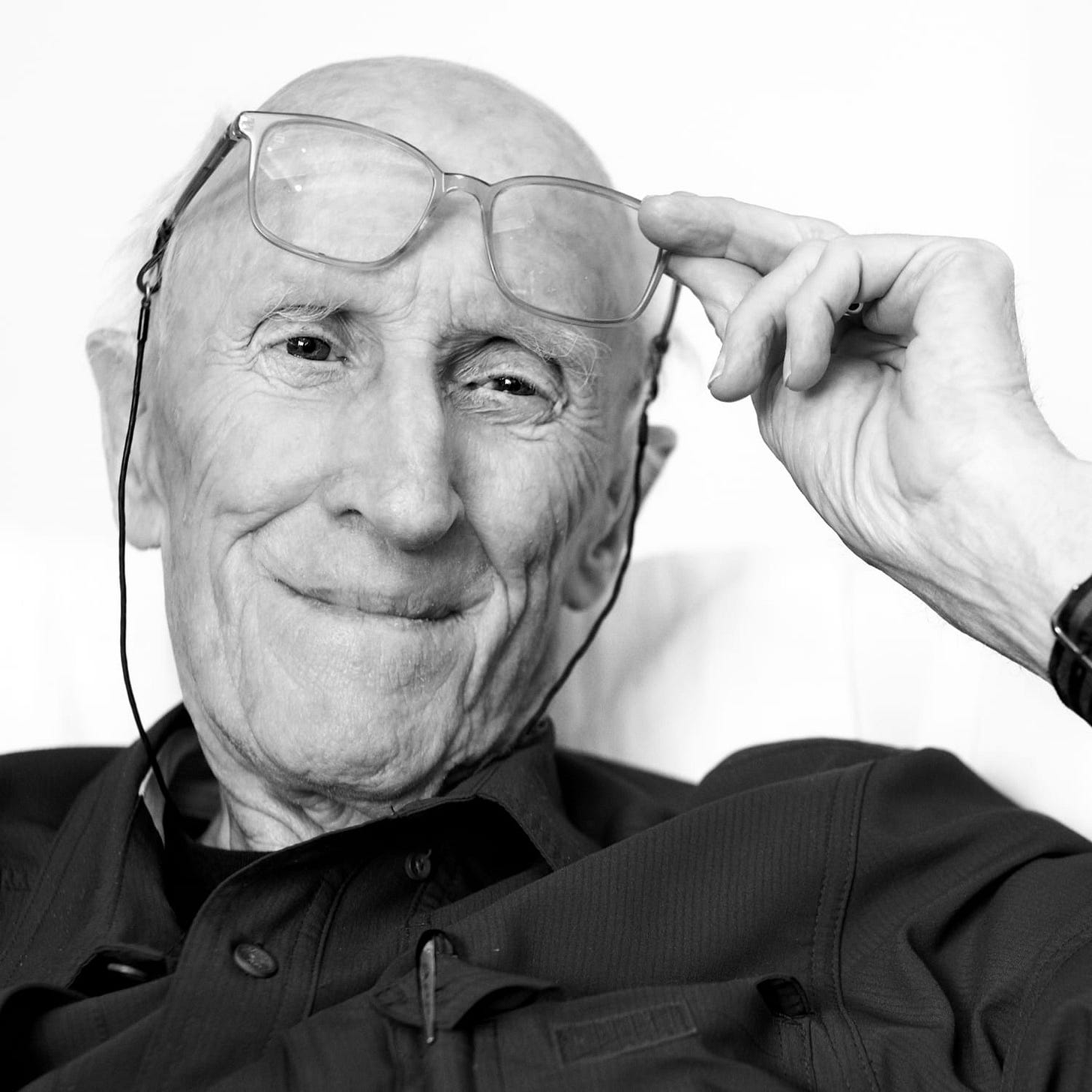

But this isn’t a typical author. Stewart Brand is one of the select individuals whom I consider a cultural progenitor of Silicon Valley. He was the publisher of The Whole Earth Catalog, a publication which Steve Jobs once called “Google in paperback form.” It was also sweeping in scope, covering everything from geodesic domes to cybernetics to organic farming, yet was meandering in execution, with its famously chaotic, magazine-style layouts that jumped from chainsaw reviews to book reviews about Zen Buddhism.

His body of work was deeply inspirational to the giants who have made the internet what it is today. He is beloved by everyone from the Collison brothers—who cofounded Stripe and published Maintenance—to Jeff Bezos. The strange alchemy of Silicon Valley, of hippie idealism, rugged individualism, and environmentalism is at least partially due to his work. The Whole Earth Catalog has little writing that will survive the centuries, but the ethos that it cultivated will resonate forever.

In a 2025 interview, NY Times opinion columnist Ezra Klein described why he reads books versus simply asking AI models for a summary of their arguments.

“I think I used to conceptualize knowledge the way you see it in the movie The Matrix, where it’s like I wanted the port in the back of my mind that the little needle would go into…I thought that what you were doing was downloading information into your brain.

Now I think that what you are doing is spending time grappling with the text, making connections. It will only happen through that process of grappling. So, the idea that you could speed run that, the idea that it could just be summarized for you...

Part of what is happening when you spend seven hours reading a book is you spend seven hours with your mind on this topic. The idea that O3 can summarize it for you, in addition to all this stuff you just will not have read, is it you didn’t have the engagement. It doesn’t impress itself upon you. It doesn’t change you. What knowledge is supposed to do is change you, and it changes you because you make connections to it.”

When considering Maintenance, I think this is the proper approach by which to read this book. I found that in marinating in its ethos, I made multiple, meaningful “connections” as Klein calls them, across the most important aspects of my life.